Sunrise

The best time of the day - faithfully reproduced

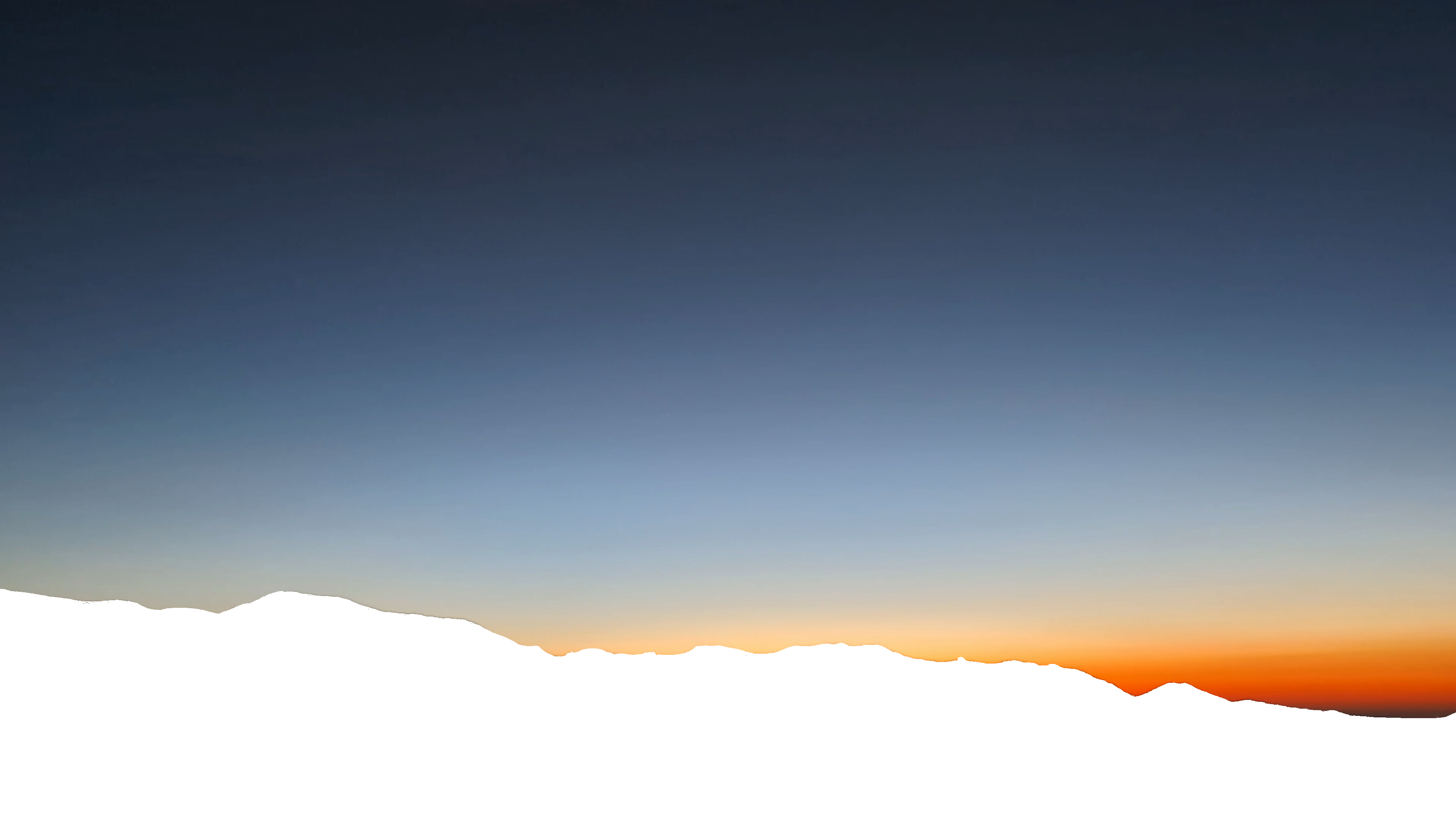

The colors of this site are copied from nature - they’re the colors of the sunrise of June 19th, 2025, viewed from RMNP. It was a good one.

Why I built this

I love mornings - they’re the best time of the day. As a new day starts, nothing has yet been decided, nature hums with anticipation - tension and potential bound up in stillness. I also love sunrises - you get to lay claim to one bookend of the day, and if seeing it being born doesn’t allow you to sieze it, I can’t imagine what could.

For several years I had the idea of trying to build a webpage that would capture my love for this moment - I knew it would be the fourth iteration of my personal site, and would soften my decade-old V3 de-stijl aesthetic. I wanted it to feel like Cory Wong’s “Trail Songs” Albums, both Daybreak and Dusk sides.

I tried many approaches without success. I tinkered around with building gradients by hand in Inkscape. I tried to build an algorithm for simulating a sunrise based off of photonic refraction for Abound. I played around in SVGator to try to figure out an animation scheme. The problem with each approach was I could never get the colors right by eye - even when I was sampling from an image of a sunrise, the colors always felt either sterile or gaudy. I realized that to emulate the real thing I needed data from the real thing. After searching youtube for videos that might suffice (without success), I decided: I needed to get a timelapse of the sky on the morning of a perfect sunrise.

Data

It took me four tries. Three times I found myself up before dawn, perched in the foothills in Colordao, looking westward into the black. But the sunrise is tricky - you have to get in position before Astronomical Twilight in order to catch it from black (which nescessarily implies doing so on a non-work day). You have to have a timelapse setup that is sturdy - and hardest of all, you get at most one shot per day. My first attempt failed when my phone was blown over by wind.

But the problem that thwarted the next two times was clouds. Clouds are tricky. They totally skew the data on colors because they introduce huge dips in saturation and skew toward bluer hues (even at sunrise). They’re also ubiquitious. If you look out to the horizon from a high vantage, only very rarely will there truly be no clouds in the sky. When visibility is good, you need sometimes hundreds of miles of clear sky in front of you to fully capture the color of the true horizon during a sunrise. Twice I found myself thwarted in the wee hours of the morning by clouds.

But then, the day before Juneteenth 2025 (the Federal holiday most worthy of celebration for other reasons) the cloud cover forecast on Open Snow indicated the holiday might be the day.

- I set an alarm for 12:55 AM.

- I packed a bag and hit the road by 1:30 AM.

- By 2:30AM I reached Rocky Mountain National Park, and was briefly delayed because none of their automated payment machines were working (sorry for not paying NPS, I tried).

- By 3:10AM I was in position at Rainbow Curve on Trail Ridge Road.

I setup the ersatz tripod (a laptop stand with a phone ductaped to it, reinforced by books - see image below),

pointing to the northeast, and slept fitfully from 3:30AM through howling winds

- During setup, I used a compass to point the camera due east, not thinking about the fact that Juneteenth is very close to the summer solstice, and thus the sun would be coming from the furthest north it ever does.

- Luckily, while still dark, the moon was rising to the east, and the crescent on the moon pointed toward the north strongly enough that I realized my error and was able to salvage the angle in time.

- I’d chosen Rainbow Curve because it points due east through the foothills, giving me a sunrise over the plains. However, because of this error, the sunrise happened over the mountains.

When I crawled out of my car to bask in the warm glow of morning, I was thrilled to see that the timelapse was perfect - you can see it here.

Building the Gradient

I got to work a few days later trying to build the CSS that could replicate the perfection of that video.

First, I used Google Photos to stabilize the result, which made subsequent analysis much easier.

Then, I created a mask which only included the sky (by hand in GIMP), and ran a bash script to extract each frame of the image and apply that mask to it. I also put any of the frames that happened after the sun poked over the horizon into a different folder. I had quickly realized it was going to be hard to solve both the pre-and-post sunrise with the same algorithm.

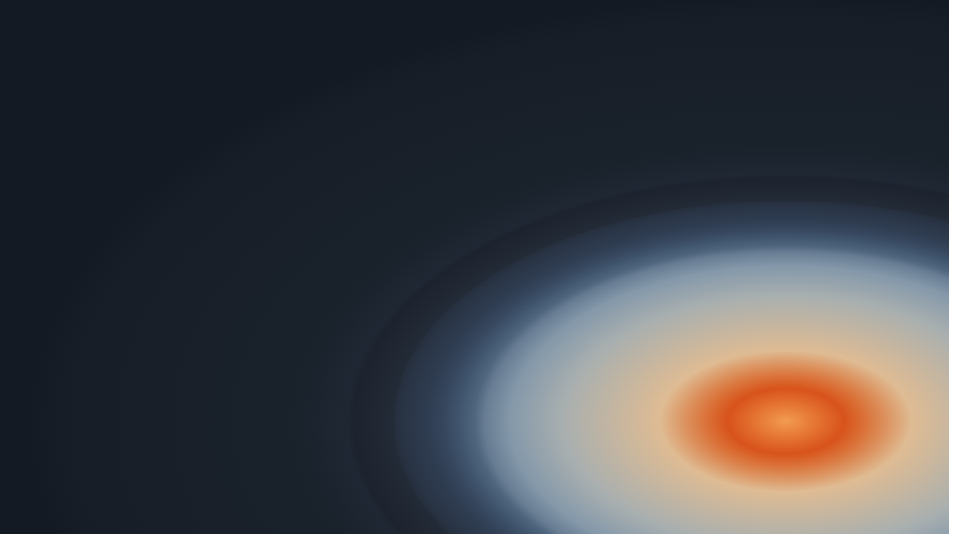

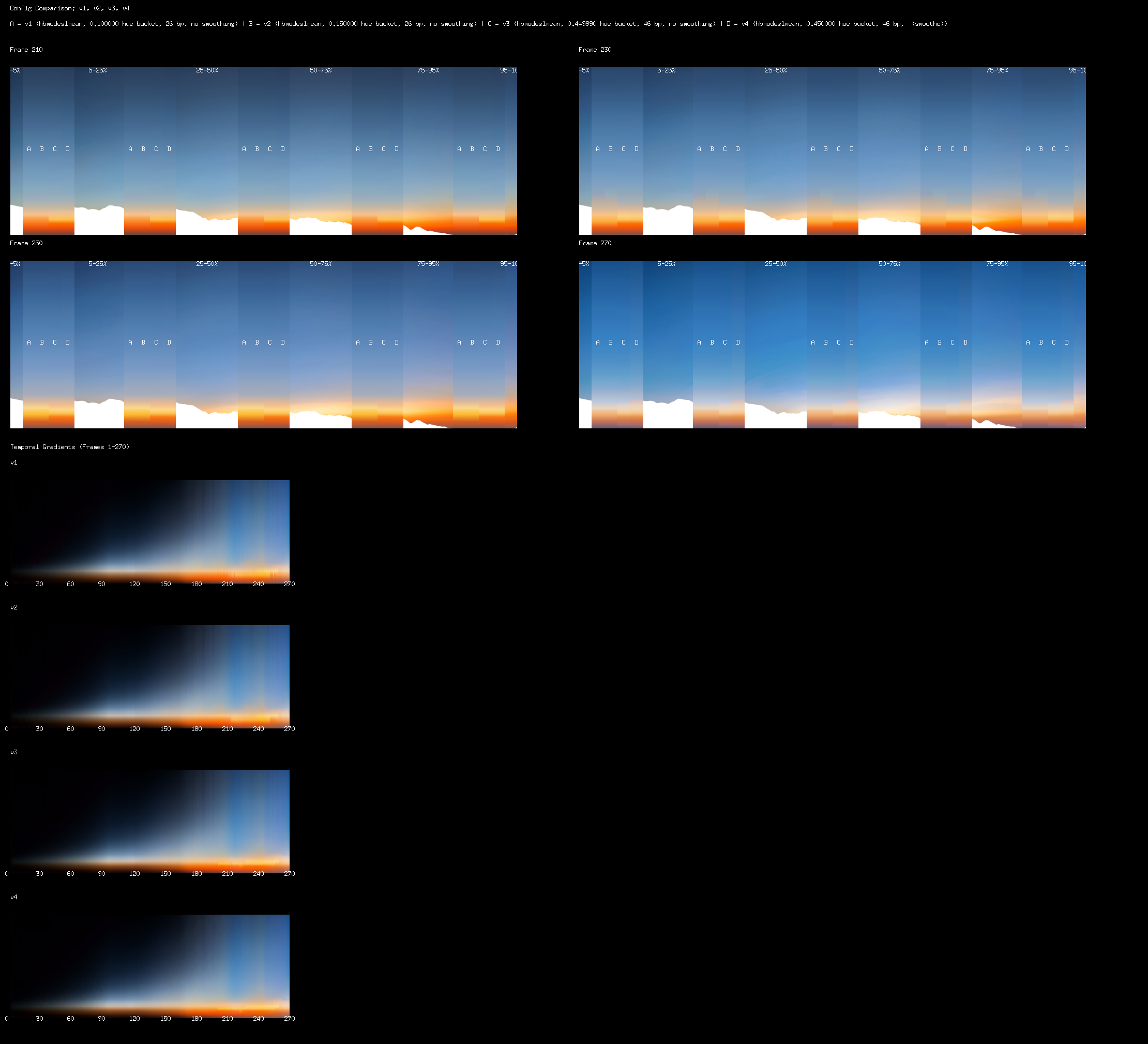

Using the data to create the output ended up being relatively simple. Using Claude Code I tried out 4-5 different algorithms that I sketched out to try to achieve the subtle curvature you see in sunrises, including:

- Using Iso-Color bands to try to identify the center of a radial gradient based on curvature

- Using a loss function (of comparison with an original frame) to try to come up with an idealized gradient for each frame

- Using a vertical color sample from the middle and edges of the image to estimate the eccentricity and center of an elipse we could use as a radial gradient.

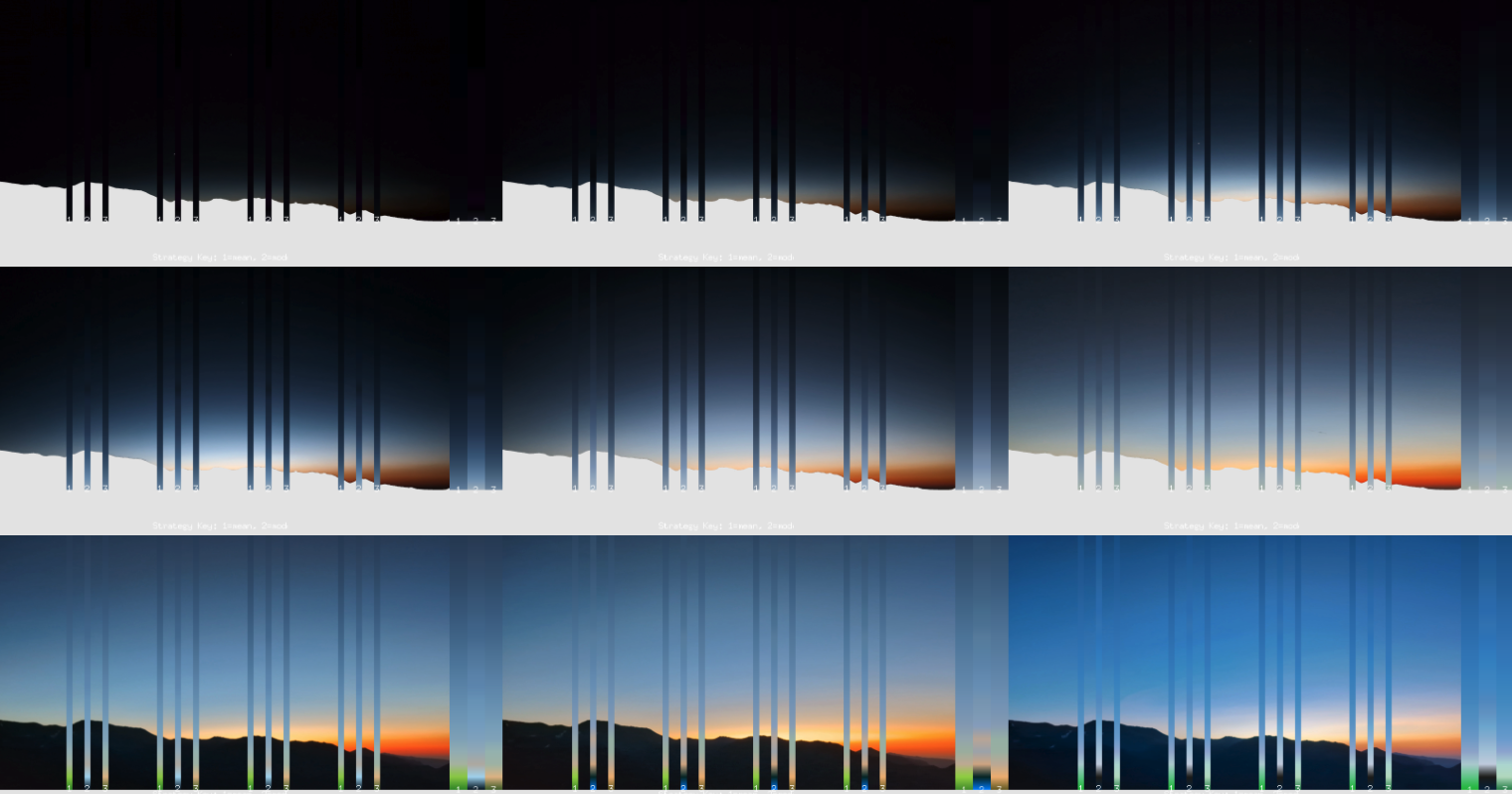

All of these proved unworkable, and while I got some fun failure modes (below), I didn’t feel like I was getting much closer.

But the more I played around with it, the more it felt like maybe a linear gradient (a far simpler approach) could be sufficient - I realized that if you add a foreground of mountains, you don’t mind the ways the light doesn’t bend as much near the horizon.

The Algorithm

So the actual algorithm is dead simple: In each frame F, select N rows evenly spaced through the frame (20-50 worked well). For each row R, average the color of every pixel in the row. This gives you an F-by-N matrix with a single color value for each cell (Row). This matrix can then be used as keyframes for the resulting linear gradient (with F being the keyframe steps). Super simple!

There are only a small number of additional effects I added after that basic algorithm. The first was recognizing that the sampling of individual rows meant that the matrix it generated wasn’t “smooth” - both in the time dimension and in the vertical dimension there was a lot of “roughness” in that the colors would jitter about and you could see the bands clearly at keyframes. I solved this through the standard box blurring algorithm (applied to the breakpoint colors, not the pixels!) - just average each breakpoint within each keyframe value with the 8 adjacent values in the matrix (2 in the same frame, 3 in the next and 3 in the prev). This reduced the amount of noise dramatically.

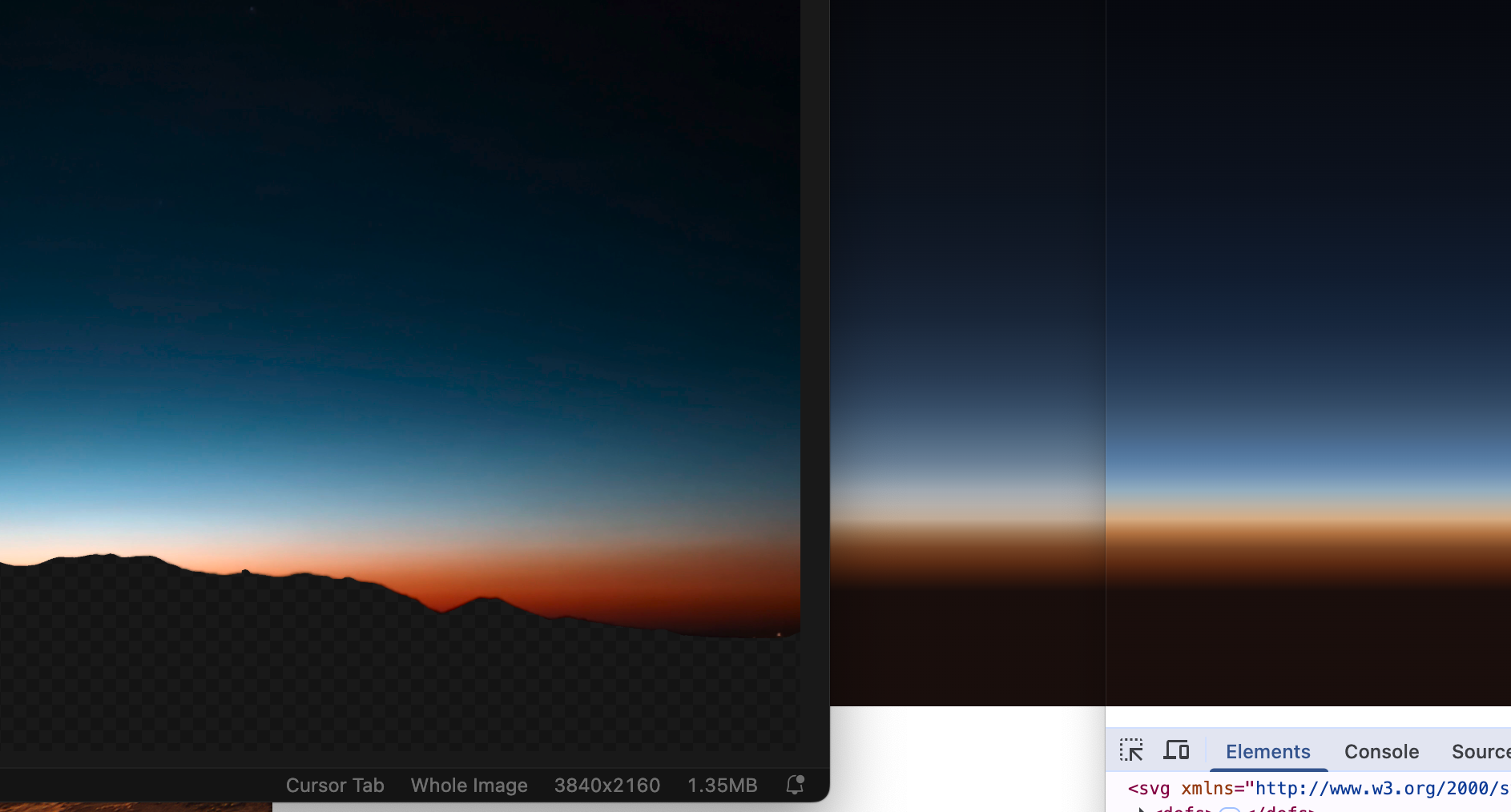

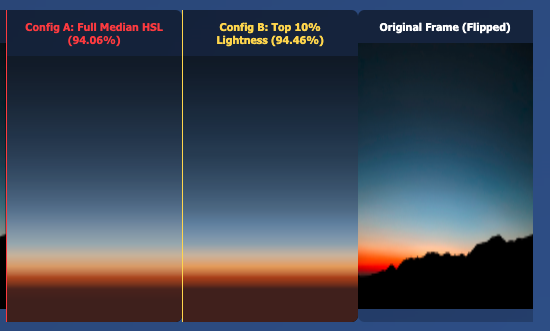

The second realization was that averaging RGB values yields colors that tend toward greys - (visualize the 3-space of the RGB cube to reason about why). HSL on the other hand doesnt suffer from this proprety (because it’s cylindrical), so I converted the logic to average based on HSL, and that dramatically improved the color fidelity. In the image below, the still frame from the video is on the left, the RGB averaged image is in the center, and the HSL averaged image (no other changes) is on the right - what a difference that makes eh!?

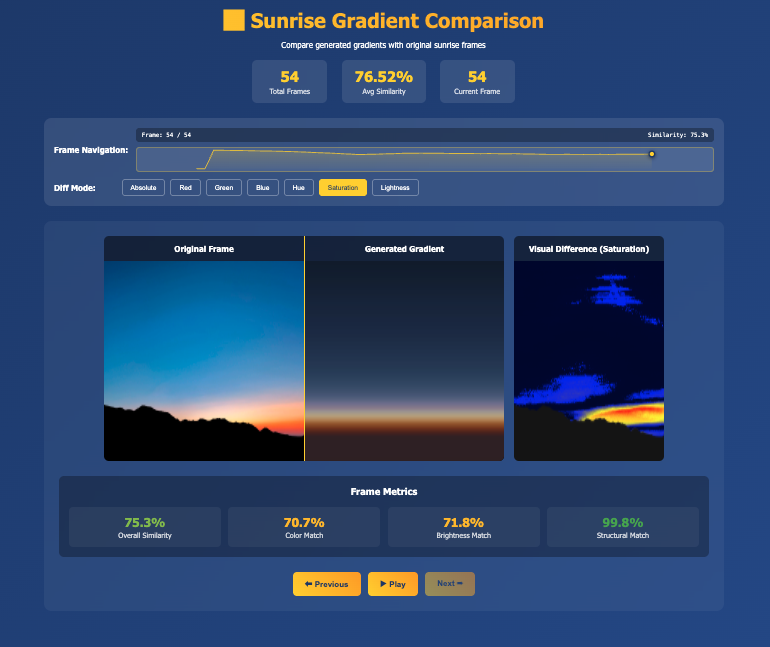

Throughout this iteration process, I built out (or rather described to Claude) a comparison tool to enable me to more effectively debug and analyze gradients. It worked great, until…

While Claude was very helpful through this iterative process, I eventually realized there was a serious issue with the color interpretation process early in the pipeline stemming from PNG color profiles somehow corrupted by my processing. Additionally, the code had become total spaghetti, there were hardcoded ideas about gamma correction, and the code was littered with the detritus of past failed experiments. I started from scratch, and built in programmatic checks at each step that the colors being generated matched (or were close to) the raw colors sampled from the image, using a different approach to image encoding and sampling, and only using HSL colors throughout, rather than doing conversions back and forth (which, it turned out were another source of lossy colors). You can see the compounded color errors most clearly in frames like this one, where the blues on the left have hues of ~219, and the blues on the right have hues closer to 201. Huge differences!

This also allowed me to rebuild the comparison tool, enabling me to quickly iterate on different approaches to averaging the pixels across a row, which I realized was the crux of the algorithm after fixing the color correction issues.

The winning algorithm is shown below, labeled as 1. It takes all of the pixels in a row and then does the following to decide the color most represenative of that row:

- The core of the algorithm is a function called “bucketize_colors”, which takes in the pixel data in the row, a “bucket_width”, and a “bucket_offset”. HSL colors represent hues as an angle between 0 and 360 degrees, like a color wheel. This algorithm would construct ranges of hues that cover the full color wheel in equal spacings, and then assign each pixel to the bucket that contains it. So for example, a bucket_width of 3 and bucket_offset of 2 would yield hue buckets like ([2, 5],[5, 8]…[359-2]), and a pixel with hue 6.22 would get put into the second bucket.

- Then, starting off with buckets of size 1, it gradually increases the bucket size until a single bucket contained more than 15% of all of the pixels in the row, searching all bucket_offsets for a given bucket_width to find the best fit if more than one offered 15% capture of the pixels.

- The pixels in this bucket were then taken as the most representative pixels in the set, and we just returned the average of their Hues, Saturations, and Lightnesses as the HSL value for the row.

You can see this algorithm in action below. #1 is this “Hue Bucketed Mean” method that I described, while #2 is a pure HSL averaging approach.

The CSS

After finishing the algorithm and finding the right sets of gradients for each frame, I needed to figure out how to render it on a website in a way that is pleasant.

Landing Page

For the landing page, there was the small matter of tricking CSS into being willing to render an animated gradient, because the specs will tell you that linear gradients aren’t animatable. Because of this I started out by using SVG animations, which worked great, but wasn’t easy to pause or replay using Javascript, and that felt important to get right.

Well, it turns out if you use CSS’ @property declarations with type color, and then animate

all of the properties that impact the linear gradient in the same set of keyframes,

CSS is willing to render a linear gradient as if it is animated. Many thanks to

Temani Afif for this very nifty hack.

Project Pages

For the project page, while talking with my dad I realized that I could use the height of the page to represent time, and try to show the transition between frames as the user scrolls down the page, just like projects tend to become clearer the further you get into them.

Implementing this was relatively simple: the page is divided into sections (per paragraph, heading, etc), and each section has two linear gradients that go from left to right. The first is a solid background, which corresponds to the linear gradient at the top of the block. The second is a linear gradient from the next block (the top of the next block) which increases in opacity from zero at the top of the block to one at the bottom of the block, so that we get a smooth color transition within each block, and because the top of one block is the same as the bottom of the next block, the transition is relatively seamless.

List Pages

I’m not satisfied with any of my current approaches to the list page - I expect I’ll iterate on it for a while until I find something I like.

The Real Author

One big disclosure I need to make about this project is that I didn’t write much code for it - mostly just describing and debugging algorithms. Though I described how they should work, Claude built all of the algorithms in several thousand lines of Golang without much assistance. If I had to build it from scratch myself, building the image processing toolkit would have taken me much more time and I would have had many more bugs than if I hadn’t relied on Claude (though, Claude still had a variety of bugs that required me to dive deep and understand its code, and in the more than one case, start from scratch). As a result, the site was quick to build, and I think it looks really nice, but under the hood it’s quite grotesque - code that carries the scars of dozens of substantial revisions by multiple authors (me and Claude) without much continuity of thought. An instructive co-programming session.

One key finding from the project is that if you’re vibe coding, you need to build out (or have Claude build out) robust processes for validating the work that it tries to do. I found building out this algorithm comparison tool was the key to making consistent progress and evaluating “success” (check out a sample output by clicking below). As we start to rely more on LLMs, have clearer ideas of what we want, and better tools to evaluate how we’re doing against those goals is going to be more and more important,

The End Result

I really like it. I like watching it. It’s a personal brand I feel connected to and proud of. It feels thoughtful - not overdone, not sloppy. Purposeful, data-driven, gorgeous. Even so, I felt ambivalent making it my new homepage - I really liked the old site.

I have a list of things I’d like to try to get working in the future, including a true radial gradient (in particular to capture the 3-5 second range of the original video here), getting the same view later in the year (when the sun will rise in the gap in the mountains instead of over them), and trying a different angle/vantage to capture the impact of alpenglow on the atmosphere.

But this is good for now. The day is young and there is much to do!